Gillander House, Kolkata

Scots Everywhere

As one takes a look at the Calcutta streets – Minto Park in South Calcutta, Dalhousie Square in Central Calcutta and Duff Street in the North – it is impossible to ignore the legacy of the Scots in the city. From the physician William Hamilton who famously cured the emperor Farrukhsiyar and procured the trading firman for the East India Company in 1717 to the Scottish jute barons of Calcutta in the early twentieth century, Scots have been influential in shaping in the fortunes of the city. Trade, the institutions of law, education and politics have all been significantly shaped by the Scots who contributed hugely in these areas.

Some of the key Scottish names that are unmistakable in Calcutta are those of Andrew Yule (the famous Scottish firm that is now a government undertaking), Gillanders Arbuthnot Co. (which has now been incorporated into the Kothari Group of Companies) and Martin Burn (now another government firm). The Scottish Church School and College near Urquhart Square; the Duff Church and the grand St. Andrew’s Kirk are reminders of the influence of the Scots in Bengal. Many Scots themselves made their fortunes in India and often found India a better option than England where they were ‘likely to be suspected of Jacobitism or […] poaching on English patronage service’ (Bryant: 1985). The lure of returning to Scotland as rich ‘nabobs’ was also fairly strong and many Scots did return home very rich men as buildings such as the Monteath Mausoleum near Edinburgh testify. The Scottish connection is best described by Sir Walter Scott, who writing to Lord Montagu in 1821, calls India ‘the corn chest for Scotland where we poor gentry must send our younger sons as we send our black cattle to the south.’ Alex M. Cain states that:

For two centuries, Scots ruled and fought in India, practiced medicine, founded missions, studied the flora and fauna, investigated its antiquities and recorded its history. They came from every part of Scotland, from Highlands and Lowlands […] from the highest families to the lowest. (Cain 1986:7)

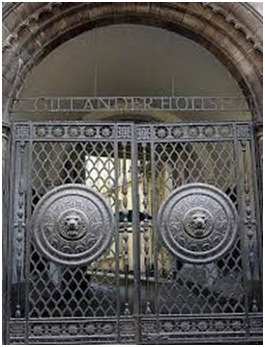

Hamilton’s epitaph

What follows is a very brief history of the Scots in Bengal. Commenting on the spread of Scottish ideas, RanajitGuha feels that it is ‘small wonder then that Scottish thought under the full impact of Enlightenment should have overflowed and spilt into areas far out in the world’ (Guha, 1982: 22). Guha goes on to speak about how adventurers such as QuintinCrauford, travelling in India in the 18th century or Alexander Dow, one of first planners of the permanent settlement of Bengal according to Guha, managed to bring European ideas to India and to introduce India to Europe.

Adventurers and Pioneers

The Scots forayed into India mainly after the failure of the Company of Scotland and the Scottish imperial venture at Darien. In the early years, the East India Company played a pivotal role for Scots in the Far East, up until it lost its trade monopoly in 1813. In fact so many Scots had found employment in the East India Company’s administrative, military and maritime services, that George Bogle (sent by Governor-General Warren Hastings as official emissary to Tibet) write home in 1771, “There are now so many of my countrymen here that I am, every now and then, meeting with an old acquaintance”.

William Hamilton’s name is legendary in the annals of the East India Company. Hamilton was part of an East India Company delegation to the Mughal court and he was able to cure the Emperor Farruksiyar of a ‘malignant distemper’; the grateful emperor allowed the British to trade duty-free in the state of Bengal. Hamilton died in 1717 and is buried in St. John’s Church. Another Hamilton is famous for his detailed accounts of Bengal around this time. Alexander Hamilton’s account of the East Indies was one of the key sources of information on Bengal at this time.

Lord Dalhousie

Enlightenment, Empire and Controversy

During the subsequent years, much of the governance of the East India Company was in the hands of another Scotsman, Henry Dundas, Viscount Melville (1742 – 1811). Dundas (also derisively called ‘Henry IX’) was a very controversial figure and also the centre of a web of patronage. He had been accused in his day of introducing Scots in India to further his management of Scottish electoral politics, by exploiting his position as member of the Board of Control of the East India Company, and the government’s political manager in Scotland.

In contrast, one must mention the three key Scottish figures influential in bringing both military victories and administrative stability to the Company’s rule. Sir John Malcolm, Sir Thomas Munro and the Hon. Mountstuart Elphinstone are together known for their efforts establishing the Indian empire according to the ideals of Mill and also of Scottish Enlightenment, and giving rise to a school of thought that remained dominant throughout the period of British rule in India. Another key and controversial Scottish statesman who had a tremendous influence on Indian culture and education is Lord Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800 – 59). Macaulay lived for a time in Calcutta (in what is the Bengal Club today) and in his controversial Minute dated 2nd February 1835, he asserted, ‘I have never found one among them who could deny that a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia’ and was instrumental in promoting a Western curriculum as the preferred form of learning and teaching.

Governor-Generals , Viceroys and Independence

Six of the governor-generals and viceroys to rule India were Scottish. Lord Minto and Lord Dalhousie ruled India as governor-generals. The latter was known for his unpopular ‘doctrine of lapse’ policy and the outbreak of the events of 1857, also called the ‘first war of Indian independence’. The railway system in India was introduced during Dalhousie’s tenure. Among the Scottish viceroys were the 8th and 9th Earls of Elgin, the Earl of Minto and Lord Linlithgow.

Scots had played a seminal role in the annexation and administration of India. Alexander Grant had fought alongside Clive at the Battle of Plassey in 1757, Sir Hector Munro of Novar had participated in the Battle of Buxar in1764(which effectively ensured the Company’s annexation ofBengal) and Sir Campbell was the leader of an army largely responsible for crushing the 1857 uprising. Mention can also be made of Col. Colin Mackenzie, India’s first Surveyor-General; Alexander Dow, Orientalist, writer, playwright and Colonel in the British army; and David Anderson, Indian revenue expert, who negotiated an end to the Anglo-Maratha War of 1772-82.

According to Ferdinand Mount, ‘In 1826, a date by which British power had only just been consolidated over the whole territory of modern India, Elphinstone was already foreseeing the end of Empire – indeed, taking it for granted.’ (Mount: 2015). Just over half a century later, a Scottish civil servant, Allan Octavian Hume, was instrumental in setting up the Indian National Congress – the party that would be the major force in the struggle for Indian Independence.

Revd. Alexander Duff

Missionaries and Educators

Of the missionaries who came to India, there were few who could parallel the activities of Rev. Alexander Duff (1806 -78). Duff had distinguished himself as a student at St. Andrews University and had come to India as one of the first missionaries of the Church of Scotland. Together with Raja Ram Mohun Roy, Duff was an early proponent of social reforms and was also instrumental in setting up the Scottish Church College. He also played role in the establishment of the Calcutta University, which owes is examination system and emphasis on physical sciences to Duff’s influence. He was a proponent of the “downward filter theory” regarding western education, who propounded his ideas on vernacular and English education in a pamphlet entitled A New Era of the English language and Literature in India. Duff was also involved in the great rift within the Church of Scotland and afterwards, constituted the Free Church of Scotland in Calcutta. The Free Church of Cornwallis Street established by him for use by Bengali Christians living nearby has been renamed after him.

Another extremely influential Scotsman in the history of education in Bengal is the former clockmaker, David Hare (1775 – 1842). Hare was instrumental in founding the Hare School, the Hindu College (now Presidency University), the School Book Society and also a society for women’s education.

The Scottish Free Church Mission also started a Zenana Mission in Calcutta in 1855, for spreading western education among women, at a time when education for women included both reading skills and needlework. The person credited with teaching women at a large scale here was Hannah Catherine Mullens, lionized in missionary histories as ‘The Apostle of the Zenanas’.

Perhaps, the most prominent (and controversial) name in the history of education in India is that of Thomas Babington Macaulay. Lord Macaulay’s Minute on Indian Education of February 1835 claimed the superiority of English education over ‘Eastern learning’ and determined the trajectory of public education in India for over a century.,/P.

Science and Industry

The first Botanical Garden in Asia was set up by Lt. Colonel Robert Kyd in his sprawling garden house at Howrah (near Calcutta) where he planted teak as well as exotic and ornamental plants. After his death, this endeavour was continued by another Scotsman, Dr William Roxburgh. Roxburgh, in consultation with Sir Joseph Banks (who had accompanied Captain Cook on his travels), brought many more species of plants to the Botanical Garden and also sent back plants to Britain. This was also a time when politics went hand-in-glove with exploration and another Scotsman, George Bogle, who was sent by Warren Hastings on an official expedition to Tibet, met the Panchen Lama and documented his journeys in Bhutan and Tibet.

The history of British industry in India is one where, again, the Scots are of paramount importance. The stories of the tea and jute industries begin with the Scots, while trade in opium and indigo, two crops that formed part of the East India Company trade monopoly, were also dominated by Scots. Mackenzie Lyall& Co. held the monopoly of opium sales for a long time in the history of the East India Company, while Mackinnon, Mackenzie and Co. had a sizable contribution in the Glasgow-Calcutta trade in cotton goods. Writing of the British community he encountered while visiting Bombay in the 1860s, Sir Charles Dilke was struck by the prominence of Scots within the business classes of one of India's largest cities, as well as throughout the British Empire, exclaiming, ‘the Bombay merchants are all Scotch. In British settlements, from Canada to Ceylon, from Dunedin to Bombay, for every Englishman that you meet who has worked himself to wealth from small beginnings without external aid, you find ten Scotchmen. It is strange, indeed, that Scotland has not become the popular name for the United Kingdom.’ [Dilke, 1888: 525]

Jute in Bengal

By the 1750s-60s, Scots formed a distinctive business group in London (many of them Jacobites), of whom many were large East India Company stockholders involved in Company politics and Indian affairs. Alongside free merchants, they seized upon the mercantile opportunities, and the Scots gradually filled several niches by acting as agents, merchants, bankers, shippers and insurers. Some ran agency houses involved in inland trade, while others played an important role in indigo, sugar, cotton and opium trades by acting as moneyed middlemen between Indian peasants and the Company. In time, the very existence of the company in India came to rely upon the silver paid into the canon treasury in return for opium and raw cotton, in whose trades Scottish traders were directly or indirectly involved. B R Tomlinson maintains that it was through this ‘international integration in trade and finance’ that the Scottish elite had encouraged ‘the process of globalisation that promoted the Industrial Revolution in Britain’ (Tomlinson, 2003).

Tea was discovered in Assam in 1823 by the Scottish explorersCharles and Robert Bruce, who was told about the plant by the local aristocratManiramDewan. This meant that a valuable commodity, previously a Chinese monopoly, could now be domesticated within the British Empire. Following their discovery and initial British skepticism, the Assam Tea Company was founded in London followed by the Williamson Company and the Jorehaut Tea Company. In 1848, Thomas Lipton’s Tea Company became the largest company trading in tea by the late 19th century. A reminder of the Scottish heritage of Assam tea, Kolkata still boasts of a ‘Scottish Assam India Limited’ at Crooked Lane, Esplanade.

Owing to its unique geographical conditions, Bengal had an effective monopoly in the production of raw jute, and this had drawn the interest if the east India Company, in early 20th century, the Company started trading raw jute with Dundee in Scotland, but the urgent need of jute sandbags during the Crimean War made it imperative (and cheaper) to introduce factories on Bengal. The first jute mill was established at Rishra in 1855, when George Acland brought jute-spinning machines from Dundee. Until the mid-1880s the jute industry was confined almost entirely to Dundee and Calcutta, and by the First World War Calcutta (and its hinterland) had 38 mills with 184000 workers, of whom 1000 were Scots. This ended up ‘transforming Calcutta from a trading and financial into a manufacturing centre’ (Fry, 2001: 325). Some of these jute companies were Andrew Yule and Co, Thomas Duff and Co, Victoria Jute Factory Co, Samnuggur Jute Factory Co, Titaghur Jute Factory Co and Angus Co.

Conclusion

Several illustrious Scots have been commemorated in the street-names of Calcutta. These include Elgin Road (after the 9th Earl of Elgin Victor Alexander Bruce, Governor-General of India, 1894-99), Minto Park (Earl of Minto, Viceroy of India 1906-10, and author of the Minto-Morley Reforms of 1909), Dalhousie Square (after Governor-General Dalhousie), Duff Street (after Rev. Alexander Duff) and Kyd Street (after Col. Robert Kyd, founder of the Botanical Garden). In the course of history several other Scottish personages who do not fall within the ‘great-men’ model but have nevertheless played a seminal role in the fortunes of the city have fallen into obscurity, and it is the aim of this project to resurrect their memory.

References:

Bryant, G. J. “Scots in India in the Eighteenth Century.” The Scottish Historical Review 64, 177 (April 1, 1985): 22–41.

Buettner, Elizabeth. "Haggis in the Raj: Private and Public Celebrations of Scottishness in Late Imperial India."The Scottish Historical Review (2002): 212-239.

Cain, Alex M. The Cornchest for Scotland: Scots in India. National Library of Scotland, 1986.

Dilke, C. W. Greater Britain: A Record of Travel in English-Speaking Countries During 1866 and 1867, (London, 1888; originally published 1868).

Furber, Holden. Henry Dundas: First Viscount Melville, 1741-1811, Political Manager of Scotland, Statesman, Administrator of British India. Oxford University Press, H. Milford, 1931.

Guha, Ranajit. A Rule of Property for Bengal: An Essay on the Idea of Permanent Settlement. Orient Blackswan, 1982.

Fry, Michael. The Scottish Empire (East Lothian: Tuckwell Press and Edinburgh: Birlinn Ltd, 2001)

Mount, Ferdinand. The Tears of the Rajas: Mutiny, Money and Marriage in India 1805-1905. Simon and Schuster, 2015

Munro, J. Forbes. Maritime Enterprise and Empire: Sir William Mackinnon and His Business Network, 1823-93. Boydell Press, 2003.

Sharma, Jayeeta. Empire’s Garden: Assam and the Making of India. Duke University Press, 2011.

Stewart, Gordon Thomas. Jute and Empire: The Calcutta Jute Wallahs and the Landscapes of Empire. Manchester University Press, 1998.

Tomlinson, B R. “Current Research”, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London, 2003.