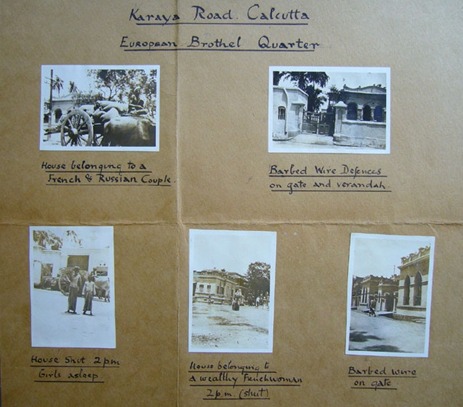

Kareya Road in the early 20th century

Introduction

Park Street was originally known as Burial Ground Road and with the grand South Park Street Cemetery, the now-destroyed North Park, Mission and Tiretta Cemeteries and the sprawling and still-in-use Lower Circular Road Cemeteries, the name would indeed make a lot of sense. Sir Elijah Impey’s deer park, of course, gave its much pleasanter name to the street and from being part of the early British white town, the locality has still maintained its status as the posh arcade of twenty-first century Calcutta (or Kolkata, as the city has been renamed). Just across the road and a short walk away from the South Park Street Cemetery and its famous tombs of Sir William Jones, Rose Aylmer and ‘Hindoo’ Stuart, one finds the Scottish Cemetery, earlier known as the Scots and Dissenters’ Cemetery, Calcutta.

The cemetery is not too easy to spot and one needs to turn into the rather narrow Karaya Road, once notorious as the European red-light quarter. A two-minute-walk down the road past motor-garages takes you to the Scottish Cemetery. The cemetery is now under the supervision of St. Andrew’s Church, Dalhousie Square and conservation work is being carried out by the Kolkata Scottish Heritage Trust (KSHT). Visitors are welcome from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m. and need to contact the caretaker to get inside.

From the early 20th century

A Cemetery of Their Own

In a petition signed by the Kirk Session Elders in 1820, it was stated that ‘in every place, people, countrys [sic]or of different religious persuasions have always separate Burial Ground for themselves.’ It was also pointed out that burials in the English Burial Ground were too expensive and a subscription was called for land to be used as the Scottish burial ground by the elders, comprising J.W. Fulton, A. Colvin, G.I. Gordon, A. Mactier and E. Brightman. E.S.Wenger in his History of the Lall Bazar Chapel writes of a letter from Revd. James Bryce, the pastor of St. Andrews, to the Baptist minister, Rev. Lawson, thanking him for his donation of three hundred sicca rupees. Wenger states that the area of the church is 9 bighas (1621 sq. metres). He further notes that extra money had to be paid by Rev.Gogerly to bury his infant son as due to some misunderstanding between the independent church and the officers of the Scotch Kirk the burial took place in the portion allotted to the Circular Road Church.

There was some controversy regarding the rights of other denominations to bury their dead in the cemetery as the Kirk Session had raised objections. Later, the area to be used by the respective denominations was agreed upon by the ministers from the various denominations. The church registers go back only up to 1840 but the first recorded burial is that of Margaret Boyd, the wife of the merchant W.S. Boyd of Boyd, Beeby & Co. who died in 1826. John McKean, who died a month later is also buried there.

Some Important Graves

Rev. George Gogerly, mentioned earlier, contributed to the history of printing in India before he went back to England as a pastor in Melton Mowbray leaving his infant son buried in the Scots Cemetery. Many Britishers who had a significant contribution in the history of Calcutta and are now largely forgotten are buried somewhere in the city or have some of their relatives buried in its many cemeteries. The Scottish Cemetery has many names that were important in their own time and even later.

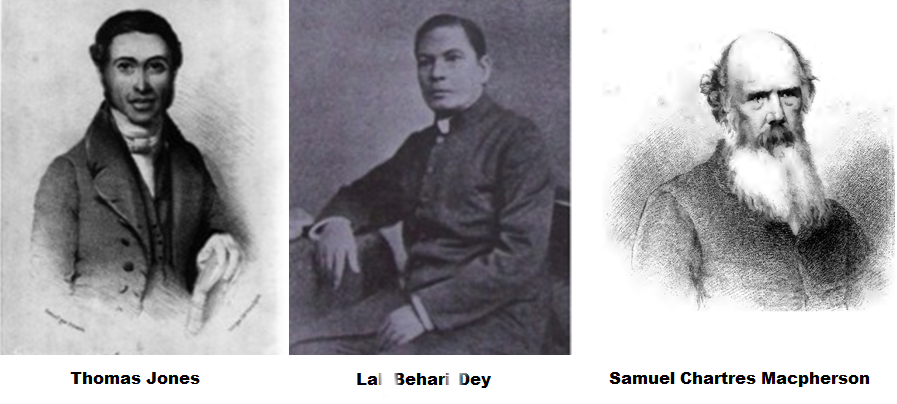

The most visited grave in the cemetery is that of Rev. Thomas Jones, who introduced the Roman alphabet into Khasi language and thus is the main creator of the Khasi script and its literature. One of the other key names that come to mind is that of Samuel Charters Macpherson who stopped human sacrifice among the Khond tribe in Orissa. William Hopkins Pearce, the son of the famous preacher Samuel Pearce, was a pioneer of women’s education and of translating English texts into Indian languages. Rev. David Ewart who was the first pastor of the ‘Bengali’ Church is buried here. John James Robson Bowman, whose father designed the coat-of-arms of Australia, is another notable name. So is Simon Nicolson, the surgeon to the governor-general who was called ‘the Sir H. Halford of Calcutta’ is another famous person buried here.

The son of the well-known Indigo planter, James Forlong, is buried in the cemetery. Forlong was part of the debates that raged during the ‘indigo revolt’ and was called the ‘white sheep in a black flock’ by the Hindoo Patriot newspaper.

Other important names are the missionaries such as John Adam of the London Missionary Society, James Penny of the Benevolent Institution and the Bengali missionary, Radhanath Dass. Another eminent Bengali missionary and the author of Folktales of Bengal, Rev. Lal Behari Day is buried here. The family of one of the first Indian M.R.C.S doctors, Dr Dwarka Nath Basu, is buried here.

The tombs of many eminent Christians, both European and Indian, are to be found in the Scottish Cemetery. The rich history that this cemetery is witness to, is waiting to be researched.

The Cemetery and Its Expansion

In 1839, the undertaker, P. Lindemann, requested that a portion be set aside for Cutchagraves for paupers. In 1840, the ground charges were:

Ground fee for a puckagrave: 10 rupees

Ditto ………..cutcha grave: 4 rupees

When a monument is erected over a pucka or cutcha grave and does not occupy more space than the grave: 25 rupees

Additional ground fee for a cutcha grave if a monument is erected over it afterwards: 6 rupees

Charge for a puckagrave exclusive of ground fee: 80 rupees

The cemetery was extended in 1913 at the cost of around 9960 rupees, some of which was borrowed from the Bank of Bengal (now State Bank of India). The Kolkata Scottish Heritage Trust states in its booklet on the cemetery that ‘ the growth and prosperity of the Scottish business community and the strengthened activities of its missionaries, are ironically reflected in the burial registers of the Scottish Cemetery between 1825 and 1947.’

In August 1913, the Government of Bengal wrote to the Church asking for an estimate of costs for collecting information on the old tombs and monuments. In 1915, it was reported to the Kirk Session that no progress on this had been made. In 1916, the barrister Gasper Ives Gregory took over the maintenance of the cemetery and regular repairs were carried out. In November 1918, Babu R.C. Dass presented a bill of 100 rupees for a plan of the cemetery.

In 1980, in his article in Purosri, the journal of the Calcutta Corporation, Alok Ray states the following:

The cemetery is ancient but not protected at all. It is useless even to go into how such a place would have been conserved and protected abroad. […] On entering the cemetery, one notices the dense jungle and it is indeed difficult to make one’s way through the thorny bushes and the extremely uneven ground. Many of the graves have crumbled into the dust and most have been damaged and their epitaphs are almost impossible to decipher’ (Ray 1980, my translation).

Ray speaks of the importance of ventures such as the Bengal Obituary in attempting to capture the lives of the not-so-famous Britishers who lived in India and whose memories will otherwise be lost forever. He also laments the lack of such endeavours after the Bengal Obituary was published in 1851.

The cemetery in 2015

The Cemetery Today: The Kolkata Scottish Heritage Trust, BACSA and St. Andrew’s Kirk

The Kolkata Scottish Heritage Trust took over the maintenance of the Scottish Cemetery in 2008 and their website describes their progress quite clearly:

In 2008, the cemetery was cleared of invasive vegetation which sadly has been the principal cause of decay to memorials and headstones. Thereafter it was possible to conduct a detailed archaeological survey, to assess the condition of surviving monuments and consider the most effective means of repair. Much of the survey work was conducted by RCAHMS (the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historic and Monuments of Scotland).

The Trust has as its aims, the following:

1. To maintain the Scottish Cemetery as a managed green space which can serve as a ‘lung’ for the surrounding population.

2. To research and record the cemetery and thereby improve the understanding of the site, its history and its genealogical importance. To make this information available.

3. To restore the cemetery buildings and as many of the monuments as possible.

4. To establish a center for training traditional building skills necessary for the repair and restoration of the monuments as well as of the traditional buildings of Kolkata.

The Trust is chaired by Lord Charles Bruce, the descendant of the eight and the ninth Earls of Elgin who were both viceroys of India. Besides Lord Bruce, the other members of the Trust are Ian Stein, Elizabeth Guest and Prof. Bashabi Fraser. Following the appointment of Dr Neeta Das as project architect in March 2012, the Trustees commissioned the restoration of the distinctive nineteenth century gatehouse and ensured that repairs were carried out by skilled craftsmen using traditional materials including lime mortars and plasters.

KSHT works in close collaboration with St. Andrew’s Kirk and the Kirk’s website adds:

As at this date, July 2014, the vegetation, shrubs and bushes have been cleared and re-growth prevented. This has revealed all the graves and ground layout and paths are now being established and renovation of graves, headstones and memorials started. Information on the work and what is planned are on display in the gatehouse where there is a copy of the Burial Register and a Visitor’s Book.

It also mentions that the British Association for Cemeteries in South Asia (BACSA) has been supporting the project.

The Cemetery Online: The UKIERI ‘Narratives of Migration and Exchange’ Project

In 2008, members of a survey team from the RCAHMS and Simpson & Brown Architects visited the cemetery did some scoping work for an online repository and uploaded some photographs on online databases. Their blog lists the work that was done then. Building substantially on their groundwork and using our own experience in reconstructing the history of the Dutch settlement of Chinsurah through our research of the narratives of those who were buried in the Chinsurah cemetery, our project has brought an entirely new approach towards researching the history of the Scots in Bengal. Instead of merely listing monuments, their condition and taking photographs, our project also draws together various archival sources to tell the stories of people whose lives have remained untold or have been forgotten. This archive is a re-telling of colonial history from the tales of people who have hitherto rarely been heard but who comprised the major section of colonial society.

In 2014, Presidency University was awarded a grant as part of the UK-India Research Initiative (UKIERI) funding for this project on creating a digital archive of the Scottish Cemetery. Together with its partner, the University of St. Andrews and with KSHT, the project team has put together an online database that aims to recover the lost data about the Scots who lived in and in many ways shaped the culture and society of Bengal. Stitching together information gleaned from as many sources as possible, both offline and online, this project addresses the very problems that Ray had raised in his essay, way back in 1980. As an online and freely accessible archive, the website will enable researchers the world over to access a wealth of information that was unavailable earlier about this period of colonial history.